Defence Finance Monitor Digest #69

Defence Finance Monitor is a specialised source of analysis for professionals who seek to anticipate how strategic priorities shape investment patterns in the defence sector. In a landscape shaped by high-stakes political choices and rapid technological shifts, understanding the link between military doctrine, operational requirements, and industrial policy is not a competitive edge—it is a prerequisite.

We analyse how strategic imperatives set by NATO, the European Union, allied Indo-Pacific democracies, and national Ministries of Defence translate into procurement programmes, innovation roadmaps, and long-term industrial priorities. Rather than listing individual companies, we track how clearly defined strategic challenges—such as deterrence gaps, technological dependencies, or capability shortfalls—are converted into funding schemes and institutional demand. Only companies that respond to these challenges become relevant to institutional buyers and, by extension, to investors. This framework has already enabled a growing community of analysts and financial professionals to make more consistent, risk-aware decisions and to avoid costly misalignments.

Building on this methodology, we are developing a structured database of companies analysed and classified according to the strategic-technological criteria set out in our framework. Subscribing to Defence Finance Monitor therefore provides not only access to in-depth reports, but also to a continuously expanding database of European and allied defence firms assessed against clear benchmarks. Each company is positioned according to its alignment with EU and NATO priority capability areas, its contribution to European strategic autonomy, its level of interoperability and deterrence value, and its role in reducing dependencies on non-allied suppliers. Classification also covers technology readiness levels, participation in EU and NATO programmes, intellectual property assets, and dual-use applications. This allows subscribers to compare, benchmark, and identify the most strategically relevant actors within a coherent, transparent, and decision-oriented taxonomy.

Subscribing to Defence Finance Monitor means gaining access to a strategic intelligence service that connects financial decisions with defence priorities. At the core of our work is a structured database of European and allied defence companies, classified according to strategic-technological criteria such as autonomy, interoperability, deterrence, and supply chain resilience. In today’s environment, profitable investment requires more than market data: it requires understanding how limited public resources are channelled toward specific capability gaps, sovereign technologies, and the reduction of non-allied dependencies. By combining in-depth reports with a continuously expanding company database, Defence Finance Monitor enables investors to anticipate demand, benchmark firms against institutional priorities, and avoid costly misalignments.

Company Profiles & Industrial Intelligence

Strategic Innovation Financing: Public Power and Private Capital

Innovation financing has become the decisive variable in the competition for technological dominance. The ability to transform research into deployable capability now depends less on scientific discovery than on the financial architectures that sustain it. Artificial intelligence, in particular, requires vast and continuous investment in data, computation, and human capital, creating an unprecedented convergence between financial and strategic power. In the democratic world, this financing structure is largely decentralised, driven by venture capital, private equity, and open competition among firms. In authoritarian regimes, by contrast, capital is concentrated and directed by the state, subordinating innovation to political objectives. The contrast between these two models reveals a fundamental divide in how societies convert knowledge into strategic capability. The allocation of resources, incentives for risk, and tolerance for failure define not only economic growth but the speed and quality of military and technological adaptation.

The New Military-Industrial Complex of Artificial Intelligence

Artificial intelligence is transforming the traditional military-industrial complex into a new strategic ecosystem where innovation, finance, and warfare converge. Unlike the Cold War model—centred on state-owned arsenals and vertically integrated defence contractors—the new structure operates as a distributed network that merges private capital, technological entrepreneurship, and government demand. Artificial intelligence functions as the connective tissue of this ecosystem, linking research, production, and command functions through data. The result is a defence economy in which knowledge and computation, rather than steel or oil, form the critical resources of power. Governments are no longer the sole drivers of technological advancement; they are now partners and regulators in a system dominated by private entities that design, fund, and operationalise technologies with direct military relevance. This transformation redefines the very nature of strategic autonomy and shifts the balance of influence from public bureaucracies to hybrid networks of technology and capital.

Godel Technologies (Belarus/UK): Strategic-Technological Analysis

Godel Technologies is a Manchester-headquartered software engineering firm with roots in Eastern Europe, offering agile development and IT services to enterprise clients[1]. Founded in 2002, the company has grown from a niche nearshoring provider into a 1,800-strong tech organization operating across the UK and EU allied countries[2]. Godel’s journey is unique: it established development centers in Belarus during the 2000s to tap a highly-skilled programmer base[3][1], yet recently divested its Belarus subsidiary amid geopolitical shifts[4]. This transition underscores the firm’s evolving alignment with Western markets and security norms. Today, Godel specializes in custom software solutions, cloud services, data analytics and cybersecurity – capabilities increasingly relevant to Europe’s push for digital sovereignty and resilience[2]. How does a private UK software company with Belarusian origins fit into Europe’s defense-tech landscape? The following analysis explores Godel’s technological profile and its potential contributions to European strategic autonomy, NATO interoperability, and supply chain security in an era of heightened great-power competition.

Kraken Technology Group – Strategic-Technological Analysis

Kraken Technology Group is a British maritime defense innovator drawing rising attention for its high-speed autonomous vessels. Founded in 2020 amid a pivot from powerboat racing to security, the company has quickly moved from concept to operational trials. Its uncrewed surface vessels (USVs) are not theoretical prototypes but fast, mission-ready platforms already navigating Europe’s strategic waters. In recent NATO exercises and Royal Navy trials, Kraken’s sleek Scout craft demonstrated remote operation from over 150 miles away and integration into digital command networks[1]. Such early validations, combined with partnerships ranging from a 150-year-old German shipyard to cutting-edge autonomy software firms, suggest Kraken’s disruptive potential. The company’s emergence comes as Europe seeks greater technological sovereignty and agile deterrence tools. Kraken’s story – from record-breaking offshore racing to delivering affordable unmanned patrol boats at scale – offers a compelling glimpse into how home-grown European ingenuity can enhance defense autonomy and resilience.

Simera Sense – Strategic Technological Analysis

In the global race for smarter, more autonomous defense technologies, a young company with roots in South Africa is quietly making waves within Europe’s space sector. Simera Sense has emerged as a niche provider of high-performance optical payloads for small satellites, positioning itself at the crossroads of Europe’s strategic quest for technological sovereignty and the NewSpace revolution. Founded in 2018 and now headquartered in Belgium, Simera Sense develops compact Earth observation cameras that can be deployed on nano- and microsatellites[1]. This agile entrant is helping European players access high-resolution imagery from space without depending on traditional suppliers outside the EU. As NATO underscores the importance of emerging and disruptive technologies like autonomous systems and artificial intelligence for future operations[2], Simera Sense is carving out a role as a responsive innovator. The company’s story – from a Stellenbosch-based engineering team to an international scale-up with European offices – offers insight into how strategic start-ups can bolster Europe’s defense tech base. In an era when the EU is striving to reduce reliance on non-allied suppliers[3] and reinforce deterrence through technological edge, Simera Sense provides a compelling case study of dual-use innovation aligning with these goals.

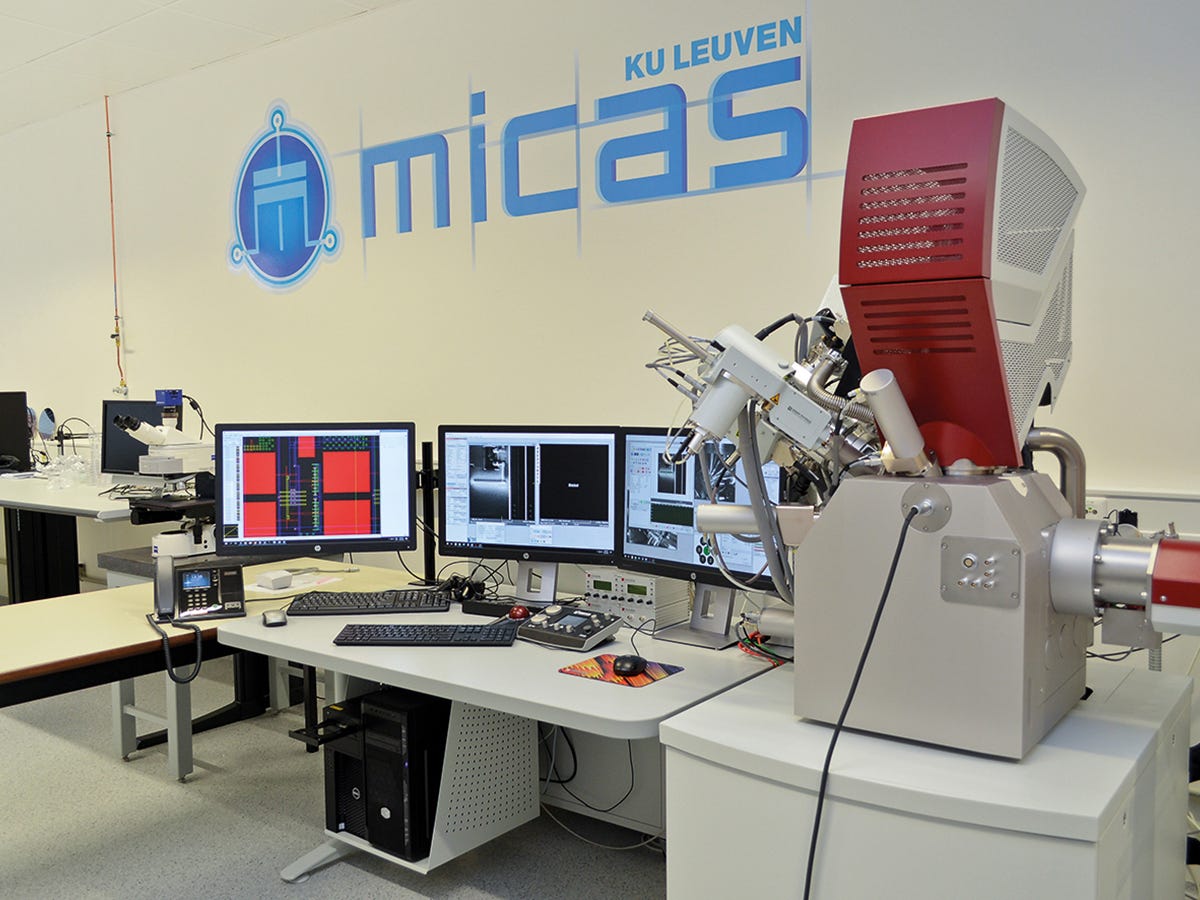

MICAS (Belgium): Strategic-Technological Analysis

In the heart of Belgium, a small research-driven organization is quietly shaping Europe’s high-tech future. MICAS – a microelectronics center at KU Leuven – is not a household name, yet its innovations power critical systems from satellites to medical devices. This academic hub has spun off multiple companies that design specialized chips, helping Europe reduce reliance on foreign semiconductor suppliers. At a time when the EU aims to double its share of global chip production from 10% to 20% by 2030, MICAS exemplifies the continent’s drive for technological sovereignty. By pioneering radiation-hardened circuits, precision sensors, and AI accelerators on European soil, it aligns closely with EU strategic autonomy goals. The following analysis explores how MICAS and its spin-offs contribute to European defense and dual-use capabilities – bolstering NATO interoperability, enhancing deterrence, and strengthening supply chain resilience – all while rooted in a collaborative university ecosystem. This deep dive will reveal an uncelebrated but crucial asset in Europe’s quest for technological independence.